Export of Sensitive U.S. Technology Slows Under Trump

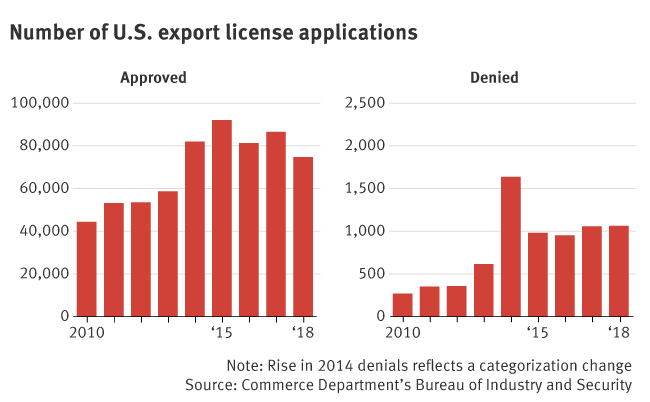

The Trump administration has made it harder for U.S. tech companies to export sensitive U.S. technologies, such as encryption software, semiconductors and drones. Export license approvals have dropped and rejections have risen in recent years, data obtained by The Information shows, and lawyers advising companies seeking export licenses say it’s taking longer to win approvals.

Still, the overall number of government-approved export licenses for technologies with both military and civilian uses far outpaces denials, the data shows. This suggests President Donald Trump’s desire to clamp down on the export of sensitive technologies, particularly to China, has had a relatively limited impact.

The Takeaway

- Govt data reveal export of encryption software, chips and drones

- Numbers show on-the-ground impact of president’s trade war

- Data show ‘chilling effect’ that political tension is having on Silicon Valley

Powered by Deep Research

All told, the Commerce Department approved more than 74,700 license applications, worth more than $64 billion, to export regulated technology in 2018, according to the data. That’s down from a high of just over 92,100 licenses in 2015 under then-President Barack Obama.

The data, which is collected by a small division of the Department of Commerce, has never before been made public. It was obtained via a Freedom of Information Act request, and The Information is making the complete dataset, including every category the government collects, available for download here. The data include the dollar amount and destination country for technologies that require government approval for export. Many of the license applications were filed by tech companies, including some that do business with Chinese firms ZTE and Huawei, which have been sanctioned by the U.S. government. We've also prepared an interactive world map that lets you explore the data by country, available here.

License denials, meanwhile, have risen since Trump took office. More than 1,000 applications were denied in each of 2018 and 2017, representing more than $1 billion in goods combined and outpacing prior years. (In the chart above, the denials for 2014 represent a change in how the Commerce Department, which grants licenses, categorizes certain types, resulting in an artificial spike that year.)

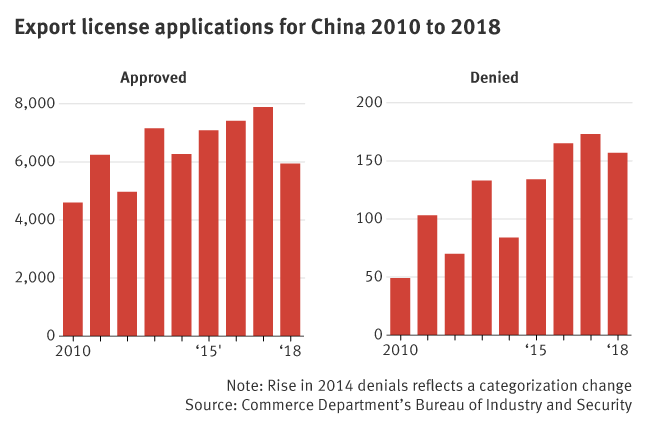

“We’ve seen slowdowns and unexpected rejections for China” since Trump took office, said Dan Fisher-Owens, an attorney at Berliner Corcoran & Rowe. “We’re seeing more rejections of national security–controlled items that would have been licensed to China two years ago, including clients who have received the same items in the past.”

A number of different exports appear to have been affected by Trump’s policies on China. Approvals of certain semiconductors and chip-related intellectual property, for example, dipped in 2018. Many of these items are at the heart of China’s “Made in China 2025” plan, which aims to have lucrative technology the country currently imports be made at home.

To put the data in context, The Information had a half-dozen experts, including former Commerce Department officials as well as lawyers who submit applications to the agency on behalf of companies, study the numbers. Among the findings that stood out:

- A number of cryptographic-related items have been approved for export to North Korea, totaling more than $1.2 million, since 2010. Experts said these were likely for use either by an allied government, for instance at an embassy, or by a humanitarian-oriented nonprofit organization. (A Commerce Department spokesman said export laws allow for “approval of humanitarian items, items supporting United Nations humanitarian efforts and agricultural commodities or medical devices that are not luxury goods.”)

- A handful of high-value IT-related goods were approved for export to Syria, items that experts say were most likely destined for NGOs working on humanitarian aid, rather than Syrian government users. (A Commerce Department spokesman said end users “would be parties engaged in activity supporting U.S. foreign policy objectives in Syria.”)

- A handful of high-end cryptographic goods were approved for export to Israel, possibly for government use, experts said. This reflects a longstanding cooperation between the U.S. and Israel on cyber and network security issues.

‘Chilling Effect’

The current political climate has had a “chilling effect” on Silicon Valley, Fisher-Owens said, adding that mid to small-size tech firms are seeking legal advice on export issues for the first time. Many of them, he said, do business with ZTE and Huawei, the Chinese hardware giants at the center of the U.S.-China trade and security policy battle in recent years. While large companies, such as established semiconductor makers, typically have export control programs with dedicated staff, many smaller tech firms “are not used to having export controls applied to them,” Fisher-Owens said.

“The figures suggest that the ‘trade war’ and Huawei-related sanctions are having an impact on export of these technologies to China,” said Robert Shaw, program director of the export control program at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies in Monterey, California. Still, Shaw noted there were dips in earlier years, “so it’s hard to definitely say that the Trump administration’s policies are the main cause.”

Attorneys who advise tech companies say that the time it takes it takes to process applications has increased. Applications used to take weeks or a couple of months to go through the Commerce Department; they now are taking upwards of three to six months—or more, the lawyers said.

Commerce Department spokesman Kevin Manning said staffing levels to process applications “has remained relatively stable over the past two years.” He added that “processing times for license applications vary depending on country, end use, end user and technology.”

The data reflects the number of license applications companies submitted—not necessarily what items were actually shipped abroad. The Commerce Department also does not release the names of applicants, making it impossible to determine which companies applied to export their technology.

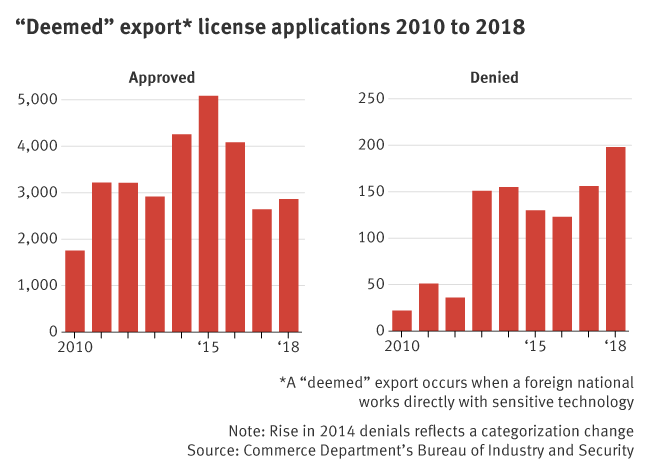

The data includes so-called “deemed exports,” which is when a company requests permission to have foreign-born citizens work on sensitive technologies. The data doesn’t denote, however, which of the applications are for deemed exports; attorneys say applications filed with nominal dollar amounts, such as $1 or $10 value, are typically for deemed exports. This makes it difficult to ascertain the true value or particular type of exports in a given year.

The Trump administration is expected to soon implement new restrictions on certain technologies, which the Commerce Department’s Bureau of Industry has spent months preparing. They will significantly expand the regulation of so-called “critical and emerging” technology, and Commerce Department officials said recently they plan to publish the new export rules by the end of the year.

The aim of the export controls and the new restrictions is to prevent these technologies, which could include everything from AI and machine learning software to 3D printing to quantum computing technologies, from falling into the hands of government-backed efforts in countries such as Syria, Iran and North Korea.